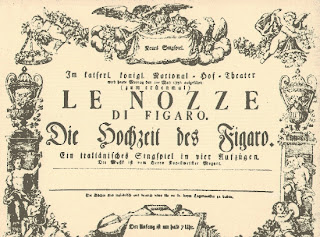

A Classic in Fine Form: Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro at the Royal Opera House

Le nozze di Figaro is, of course, a classic in the operatic canon. The cross-dressing, marriage/fidelity farce is typical of Mozart and Da Ponte in its ability to, like Shakespeare, convey both comedy and serious societal implications simultaneously. The thing is, for me, I went into this performance already weary, never having been very satisfied by either the comedy or the drama in this famous opera. I was reminded of the fact that while sometimes works can become overhyped, the crowds generally have some idea about things. I was reminded also that with something as famous as Nozze, perhaps I just had not seen a production that was good enough. That was exactly the case. This production demonstrated to me the genius of Mozart's beloved opera.

Synopsis and general information: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Marriage_of_Figaro

Le nozze di Figaro | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Credits:

Director | David McVicar

Designs | Tanya McCallin

Lighting Design | Paule Constable

Movement Director | Leah Hausman

Performers:

Conductor | John Eliot Gardiner

Figaro | Luca Pisaroni

Susanna | Lucy Crowe

Cherubino | Renata Pokupic

Count Almaviva | Christopher Maltman

Countess Almaviva | Maria Bengtsson

Bartolo | Carlos Chausson

Marcellina | Helene Schneiderman

Don Basilio | Jean-Paul Fouchécourt

Don Curzio | Alasdair Elliott

Antonio | Lynton Black

Barbarina | Mary Bevan

Chorus | Royal Opera Chorus

Orchestra | Orchestra of the Royal Opera House

___________________________________________________________________________________

The design of this production, by Tanya McCallin and Paule Constable, was an excellent take on the typical period-design production of Nozze. The primary precept of the set was the typical 18th century walls of a palace from the period. Within this, however, a section came out, contained within, to demonstrate Figaro and Susanna's room within the palace. This was quite ingenious, keeping the narrative in the same general space but specifying the room. Subsequently the room stood alone (as seen in the picture above). Finally, for the scenes in the garden, a different wall was set far back but with stylistic similarity to the palace rooms from the preceding acts, giving a sense of continuity. In each section but especially in the garden at the end, with abstracted trees and post-party items strewn about, the set and lighting had a refreshingly modern feel. It was clear that this was not a creaky old opera set, lit only with a suffocatingly suffusive warm light, from days of yore in the 20th century, despite being in period.

The design of this production, by Tanya McCallin and Paule Constable, was an excellent take on the typical period-design production of Nozze. The primary precept of the set was the typical 18th century walls of a palace from the period. Within this, however, a section came out, contained within, to demonstrate Figaro and Susanna's room within the palace. This was quite ingenious, keeping the narrative in the same general space but specifying the room. Subsequently the room stood alone (as seen in the picture above). Finally, for the scenes in the garden, a different wall was set far back but with stylistic similarity to the palace rooms from the preceding acts, giving a sense of continuity. In each section but especially in the garden at the end, with abstracted trees and post-party items strewn about, the set and lighting had a refreshingly modern feel. It was clear that this was not a creaky old opera set, lit only with a suffocatingly suffusive warm light, from days of yore in the 20th century, despite being in period.

Synopsis and general information: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Marriage_of_Figaro

Le nozze di Figaro | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Credits:

Director | David McVicar

Designs | Tanya McCallin

Lighting Design | Paule Constable

Movement Director | Leah Hausman

Performers:

Conductor | John Eliot Gardiner

Figaro | Luca Pisaroni

Susanna | Lucy Crowe

Cherubino | Renata Pokupic

Count Almaviva | Christopher Maltman

Countess Almaviva | Maria Bengtsson

Bartolo | Carlos Chausson

Marcellina | Helene Schneiderman

Don Basilio | Jean-Paul Fouchécourt

Don Curzio | Alasdair Elliott

Antonio | Lynton Black

Barbarina | Mary Bevan

Chorus | Royal Opera Chorus

Orchestra | Orchestra of the Royal Opera House

___________________________________________________________________________________

The design of this production, by Tanya McCallin and Paule Constable, was an excellent take on the typical period-design production of Nozze. The primary precept of the set was the typical 18th century walls of a palace from the period. Within this, however, a section came out, contained within, to demonstrate Figaro and Susanna's room within the palace. This was quite ingenious, keeping the narrative in the same general space but specifying the room. Subsequently the room stood alone (as seen in the picture above). Finally, for the scenes in the garden, a different wall was set far back but with stylistic similarity to the palace rooms from the preceding acts, giving a sense of continuity. In each section but especially in the garden at the end, with abstracted trees and post-party items strewn about, the set and lighting had a refreshingly modern feel. It was clear that this was not a creaky old opera set, lit only with a suffocatingly suffusive warm light, from days of yore in the 20th century, despite being in period.

The design of this production, by Tanya McCallin and Paule Constable, was an excellent take on the typical period-design production of Nozze. The primary precept of the set was the typical 18th century walls of a palace from the period. Within this, however, a section came out, contained within, to demonstrate Figaro and Susanna's room within the palace. This was quite ingenious, keeping the narrative in the same general space but specifying the room. Subsequently the room stood alone (as seen in the picture above). Finally, for the scenes in the garden, a different wall was set far back but with stylistic similarity to the palace rooms from the preceding acts, giving a sense of continuity. In each section but especially in the garden at the end, with abstracted trees and post-party items strewn about, the set and lighting had a refreshingly modern feel. It was clear that this was not a creaky old opera set, lit only with a suffocatingly suffusive warm light, from days of yore in the 20th century, despite being in period.

David McVicar's direction, combined with Leah Hausman's movement direction, beautifully set off the counterpoint of the collection of characters and dichotomy of styles in Nozze. Each character was distinctly defined, with the interpretation of the singer shining through and providing the nuance to play the range of colors each of the (at least main) characters requires. There was plenty of movement around the stage to keep things interesting and facilitate the physical comedy inherent in the opera, often with a fresh twist. The combination of casting and direction, also, helped to cast the opera in a new light, with some characters younger than often expected and others played softer, harder, etc. than typical of many productions.

Within this excellently designed set and with direction that allowed the singers to shine, the singers themselves definitely did so. Headlining the performance was Luca Pisaroni, the young Italian bass-baritone who has been winning fame around the world and whose success was noted in the Met's pastiche The Enchanted Island. His character in that production was the hulking Caliban, a character requiring much affectation to play, which Pisaroni handled ably. Here, his Figaro was exquisitely naturalistic. To say that Pisaroni played the character in any sort of revolutionary way would be to do him a disservice. This was the same old Figaro that we know and love, full of confidence in his love, wit, and cunning until the final hour. Where often that performance might feel tired or forced, however, Pisaroni felt fresh and utterly in control of the character. His voice is not necessarily over-the-top thrilling, nor the largest for a bass-baritone, but it flows smoothly and effortlessly. Every movement Pisaroni took felt as though he really just was Figaro, and his singing was at once beautiful and appropriately inflected, with vocal coloring seeming as natural as it might be in the spoken voice. Of course, nowhere was this more apparent than in big arias such as "Se vuol ballare" and "Non più andrai." Perhaps unusually, however, it was his "Aprite un po'quegli occhi," fraught with rending vulnerability, that revealed the seriousness in the opera that touches all the characters, even confident, comedic Figaro. In all, Pisaroni felt like the consummate performer - totally in sync with his own instrument and the character he was playing for the evening.

Lucy Crowe's Susanna did not initially move me, but grew on me substantially as the show went on. The voice had a kind of mellowness that was less than appealing. Certainly it is a very pretty voice, but that prettiness at times felt almost bland There is certainly a calm sweetness about the character, but initially Lucy Crowe seemed to be almost too mellow. It is hard to place exactly what changed as the performance went on. Perhaps it is that Crowe played very well the change that comes over Susanna as she becomes more assertive as the opera progresses. For some of the piece I found her simply to be inoffensive but hard to grasp. As it progressed it felt as though she had portrayed the character masterfully and that the voice fit. It is true that her "Deh vieni, non tardar" was beautiful and show-stopping. Indeed, perhaps this slow build was exactly the perception that was intended, but it was hard not comprehending that until the later acts of the show.

As Cherubino, Renata Pokupic's convincing performance was a truly immersive experience. As someone not too far away from the travails of budding amorous feelings, I was sucked in by Pokupic's at once boldly romantic and anxiously insecure Cherubino. Of course, both "Non so piu cosa son, cosa faccio" and "Voi, che sapete" express this sentiment perfectly, and Pokupic's voice rang out clearly with that perfect mix of developed female tone shaded with a boyish color. More than this, however, it was Pokupic's physical actions, oscillating between a great deal of frittering movement and a kind of martial bravado, that brought home the character.

Christopher Maltman's casting as Almaviva, combined with his acting, was quite refreshing. Certainly in many ways the joke is on Almaviva throughout the entire opera. Often times this takes the mode of a lecherous old fool chasing hopelessly after Susanna and then being flustered when he is tricked and pulled about by the rest of the cast. That kitschy interpretation has its place. Maltman's Almaviva, however, possessed a youthful vivacity that made both his pursuit of Susanna and his jealousy of his wife's presumed disloyalty believable, if still folly. Combined with a rich, commanding voice that was nowhere more striking than "Hai gia vinta la causa," it was a wonderful take on the character.

As Countess Almaviva, Maria Bengtsson offered a reserved, honest sweetness. Her singing spun fine filaments of gold with every line. At moments it did feel as though letting go of this technically masterful control and sing with a more robust tone might fit the situation, but "Porgi, amor" and "Dove sono" were heartrendingly tender. Just as the Count often has a bit of slapstick farce surrounding him so often these days, the Countess can be played as the wily seductress or as an over the top sort of caricature. Here she was exactly the pure character - hurt, longing for love, intrigued by the opportunities of Cherubino, but a woman of honor who nonetheless still possesses the cleverness to bring her husband, contrite, back to her.

Bartolo & Marcellina, played by Carlos Chausson and Helene Schneiderman, respectively, fit in the same vein for the production. So often the switch from conniving coconspirators to secret, enduring lovers is overplayed in order to make the absurdity of it acceptable. Here, Chausson and Schneiderman let the comedy speak for itself while truly demonstrating the overwhelming emotion of discovering their son and rediscovering each other. Their showpieces have less to do with this discovery, and Chausson's somewhat heavy bass handled "La vendetta" admirably although not without a catch or two while "Il capro e la capretta" sprung from Schneiderman's dark mezzo-soprano voice with surprising poignancy and tenderness.

The remaining character parts of Don Basilio (Jean-Paul Fouchécourt), Don Curzio (Alasdair Elliott), Antonio (Lynton Black), and Barbarina (Mary Bevan) fit perfectly into this well-crafted production. They played their parts, often ridiculous, quite well and sang their arias ably but were able to back away and let the surprisingly vulnerable honesty of the production reign even amongst the comedy. Indeed, Mary Bevan won particular acclaim from the crowd for her "L'ho perduta," though where she truly shined was in her gentle yet playful interactions with Cherubino. A promising outing for the young soprano.

John Eliot Gardiner led this ensemble with exceptional facility, bringing out all the best in the work's famous overture, backing off to make every word from the performers heard, and supporting a show with impeccable accuracy. The orchestra was remarkable in how symbiotic its relationship with the singers felt.

In all, the Royal Opera House's Le nozze di Figaro was splendid. It maintained the obvious comedy in Mozart and Da Ponte's masterpiece but added a humanistic side that was beautifully touching and offered reflection on the themes of marriage, love, trust, loyalty, and age. It certainly changed my mind about the work!

As Countess Almaviva, Maria Bengtsson offered a reserved, honest sweetness. Her singing spun fine filaments of gold with every line. At moments it did feel as though letting go of this technically masterful control and sing with a more robust tone might fit the situation, but "Porgi, amor" and "Dove sono" were heartrendingly tender. Just as the Count often has a bit of slapstick farce surrounding him so often these days, the Countess can be played as the wily seductress or as an over the top sort of caricature. Here she was exactly the pure character - hurt, longing for love, intrigued by the opportunities of Cherubino, but a woman of honor who nonetheless still possesses the cleverness to bring her husband, contrite, back to her.

Bartolo & Marcellina, played by Carlos Chausson and Helene Schneiderman, respectively, fit in the same vein for the production. So often the switch from conniving coconspirators to secret, enduring lovers is overplayed in order to make the absurdity of it acceptable. Here, Chausson and Schneiderman let the comedy speak for itself while truly demonstrating the overwhelming emotion of discovering their son and rediscovering each other. Their showpieces have less to do with this discovery, and Chausson's somewhat heavy bass handled "La vendetta" admirably although not without a catch or two while "Il capro e la capretta" sprung from Schneiderman's dark mezzo-soprano voice with surprising poignancy and tenderness.

The remaining character parts of Don Basilio (Jean-Paul Fouchécourt), Don Curzio (Alasdair Elliott), Antonio (Lynton Black), and Barbarina (Mary Bevan) fit perfectly into this well-crafted production. They played their parts, often ridiculous, quite well and sang their arias ably but were able to back away and let the surprisingly vulnerable honesty of the production reign even amongst the comedy. Indeed, Mary Bevan won particular acclaim from the crowd for her "L'ho perduta," though where she truly shined was in her gentle yet playful interactions with Cherubino. A promising outing for the young soprano.

John Eliot Gardiner led this ensemble with exceptional facility, bringing out all the best in the work's famous overture, backing off to make every word from the performers heard, and supporting a show with impeccable accuracy. The orchestra was remarkable in how symbiotic its relationship with the singers felt.

In all, the Royal Opera House's Le nozze di Figaro was splendid. It maintained the obvious comedy in Mozart and Da Ponte's masterpiece but added a humanistic side that was beautifully touching and offered reflection on the themes of marriage, love, trust, loyalty, and age. It certainly changed my mind about the work!

Comments

Post a Comment