Versatility At War with Categorization: An Analysis of Singers Known for Singing in Multiple Fächer

Versatility

At War with Categorization:

An

Analysis of Singers Known for Singing in Multiple Fächer

Introduction[1]

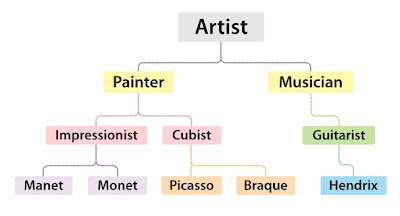

Throughout human history categorization has been an

incessant endeavor in such diverse disciplines as taxonomy, literature, and

art. It has led to great advances, such as the mapping of the human genome, and

to atrocities, such as the horrors committed in the name of race or religion.

Inevitably tension underlays the process of categorization, as marginal data threatens

to undermine the entire schematic. Categorization of singers’ voices, whether

in the German system of Fächer or by

less formal systems borne out of other nations, is essential to the vocal

world. Repertory opera houses use the system to contract singers, singers themselves

rely on guidelines for their own Fach

in the selection of repertoire, and opera enthusiasts employ the

categorizations to assess the attractiveness of performances and to review

them. Nevertheless, some singers, many among the most famous in the recorded

era, seem to defy easy categorization by voice type, switching between Fächer either at will or over the course

of a career. This tension between categorization and versatility appears to

manifest on a scale. Sopranos and mezzo-sopranos seem most disposed toward

versatility, switching both between the prime voice types and also between Fächer, tenors have great versatility

but only within their voice type switching between Fächer, and baritones and basses have less versatility available to

them. Within each of these three categories, it seems that heavier voices

roughly in the lirico-spinto range

are most disposed to singing an unusually broad range of repertoire.

Sopranos and mezzo-sopranos sing successfully in the widest

range of repertoire, succeeding both in singing across Fächer, especially as careers progress and age adds size and

strength to a voice, and also singing across primary voice types. This

differentiates them from tenors, who also master multiple Fächer but rarely venture into baritone repertoire, for instance.

As with each category, it is the soprano voices on the borderline between

heavier and lighter production that prove most versatile.

Grace Bumbry and Shirley Verrett serve as perhaps the purest

examples of the extreme border between soprano and mezzo-soprano roles,

switching between them but not so greatly between internal Fächer, sticking to dramatic roles in both. Bumbry’s performance as

Amneris in Verdi’s Aïda, for

instance, may have been in line with her beginning as a mezzo-soprano or may

have stemmed from an uncanny ability to make extensive use of chest voice.

While this kind of singing did seem to strain her a bit, it was the mainstay of

her career. In the title role of R. Strauss’ Salome, however, Bumbry was quite impressive, perhaps struggling a

bit with the uppermost reaches but bringing a gripping robustness and vigor to

the role. Similarly, Shirley Verrett exhibited capability with a variety of

mezzo-soprano roles excerpted on a recital disc, from Baroque to Bel Canto

to late Romantic. Nevertheless, across the board and even in her full

performance as Azucena in Verdi’s Il

trovatore, the voice possessed an unexpected lightness. In the title role

of Puccini’s Tosca the opposite was

apparent; while retaining squillo,

Verrett’s voice gained a dark, throbbing vibrancy. Verrett continued to sing

both dramatic soprano roles and also mezzo-soprano roles throughout her career.

While varying opinions exist about Verrett and Bumbry, these suggest both were heavier

sopranos with extraordinary capabilities in both dramatic soprano and dramatic mezzo-soprano

repertoire.

Christa Ludwig offers a similar perspective on these

dramatic switches between primary voice types, but definitively as a

mezzo-soprano with both a broader repertoire and the capability to sing soprano

roles. She excelled at lyric, spinto,

and dramatic repertoire and specialized, unusually, in both the heaviest

mezzo-soprano roles of Verdi and Wagner and also in trouser roles. For instance,

she was a favorite as Octavian in R. Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier, though her inability to personally accept the

character undermined her portrayals. She also stretched her repertoire into the

dramatic soprano realm, undertaking the Marschallin and offering a unique,

mature-sounding perspective on the role given her mezzo-soprano voice.

Nevertheless, she recognized the limits of her versatility. Though tempted by

the heavy Wagnerian soprano heroines and even urged to undertake them by

Herbert von Karajan, she eschewed them due to the strain they inflicted on her

instrument. Even among these unusual singers, this wisdom was valuable as it

avoided risks such as those undertaken by José Carreras, to be discussed in the

tenor section.

Some women exhibited extensive versatility switching between

both Fächer and also between voice

types more broadly. Rose Ponselle serves as a classic example. She had a wide

range of capabilities as a soprano, singing excerpts ranging from “Casta diva” from Bellini’s Norma to “Un bel dí vedremo” from Puccini’s Madame Butterfly and all the way to “Ritorna vincitor” from Verdi’s Aïda.

She also tackled Mozart and Wagner. Though she clearly could sing a variety of

soprano repertoire, the size of her voice, an unusual presence and warmth in

the deeper range, and a strong sense of character gave her stunning

capabilities in the title role of Bizet’s Carmen,

leading many to wonder if she should have been a mezzo-soprano all along. Poor

recording quality makes firm determinations about Ponselle’s voice difficult.

Nevertheless, she serves as a touchstone for the wide versatility of the female

voices.

Victoria de los Angeles also embodied this capability. She sang some of

the lighter soprano repertoire, notably the title role in Massenet’s Manon, and in the repertoire of Spanish

opera and zarzuela, Rossini,

Schubert, Handel, Ravel, and even Lully and Pergolesi. Her foundation, however,

was Puccini leads such as Madame Butterfly or Mimí in Puccini’s La bohéme. Despite, late in her career

she began to dabble in even heavier repertoire. She tried her hand as Elisabeth

in Wagner’s Tannhäuser, for instance,

taking on German style. Regardless of the soprano repertoire she chose to sing,

however, de los Angeles maintained the same incredible attention to detail and

capability to infuse her beautiful tone with stylistic details appropriate to

the music she sang. She too tackled the title role of Carmen, bringing to it perhaps intuitive stylistic understanding

due to her Spanish heritage. The voice clearly did not offer typical

mezzo-soprano sultriness, but made up for it with a teasing lightness. Hence,

Ponselle and de los Angeles offer even greater evidence of female versatility,

tackling everything from high, light soprano repertoire to at least the tip of

the lyric mezzo-soprano repertoire.

Maria Callas, La

Divina, sums up the section as probably the most diverse artist on the

list. Her repertoire reached from dramatic Wagnerian heroines to Bel Canto belles, with Puccini and Verdi

thrown in between. She also performed Carmen, venturing into the mezzo-soprano

realm and raising the question of whether that was where she always belonged. Ultimately

Callas seemed to possess a heavier, dramatic voice with great staying power and

exceptional range. Her success in Bel

Canto may have been due to an uncanny ability to produce a (sometimes)

pleasant tone while singing almost off the voice. This would have made the

agility and lighter refinement of this sort of repertoire easier even with a

voice that was built for roles like Tosca or even Wagnerian soprano heroines. Concurrently,

Callas’ success as Carmen makes sense, as a heavier soprano voice would be much

closer to the mezzo-soprano role than a coloratura soprano voice.

Ultimately, though the most extreme example, Maria Callas

serves as a lens for the role of female voice types in a comprehensive theory

about versatile singers. These women always possessed the capability to sing

dramatic repertoire of some type, whether soprano or mezzo-soprano. Some were

more adept at switching between those two primary voice types while others

turned more toward lighter repertoire, in both cases through mastery of unusual

instruments. Regardless, this combination of factors marks the female voices as

possessing the greatest potential for versatility.

There are tenors who succeeded in switching between primary

voice types, just as women switched between soprano and mezzo-soprano. Mario

del Monaco, Franco Corelli, and Plácido Domingo, for instance, all made

transitions between baritone and tenor. These transitions, however, were in all

cases due to inaccurate early training and in the latter case also a transition

to accommodate age. More typical for tenor voices is extensive switching

between Fächer within the tenor voice

type. Certainly many singers, such as Luciano Pavarotti, Jussi Björling, or Fritz Wunderlich, exemplify this

capability, singing Bel Canto, Verismo, and Verdi repertoire, as well

as extensive art song. Tenors, while quite versatile, especially with lirico-spinto roots, lack the

versatility of switching between primary voice types that makes women the most

versatile group.

Georges Thill was a great proponent

of French music of all periods, singing repertoire ranging from Gluck and

Charpentier to Berlioz and Massenet. His style ranged somewhere between a

typical Italianate production and something distinctly French, depending on the

repertoire. He was noted as being successful in both lyric and spinto repertoire. His lighter

selections, particularly in French music, were remarkable because they

exhibited more controlled vibrato, extensive use of timbre shading for effect,

masterful control of dynamics with superb crescendi

and diminuendi, and a solid sense

of style. Even the heavier pieces in both the French and Italian repertoire did

not entirely lose this sense of smooth French style, but Thill did allow the

vibrato and thrust of the tone to run more freely in these excerpts. Despite

this measured approach, Thill’s voice also exhibited many of the typical traits

of a more dramatic tenor voice. As he transitioned through the passaggio the voice became more

metallic, not losing depth, but turning that depth into something colder and

steelier. High notes, though secure at least in these recordings (critics

claimed they were not always so), definitely had a very hooked-in, robust

production. Thill seems to fit in the middle ground of lyrico-spinto, not unlike Jussi Björling, who possessed a vaguely

similar voice, or Luciano Pavarotti. This, combined with the success of those

singers in singing the same versatile range of repertoire adds credibility to

the theory that that sort of voice spawns versatile singers.

José Carreras offers an example of

the potential costs of versatility. Unlike Christa Ludwig, when Herbert von

Karajan approached him about undertaking heavier spinto and even dramatic tenor roles, Carreras charged

wholeheartedly into the repertoire. In one of his lightest roles, Leicester in

Rossini’s Elisabetta, regina

d’Inghilterra, abnormalities in Carreras’s production were immediately

apparent. It had the smoothness of a lyric voice but the upper range was

attacked in an almost shouted, if still covered, fashion, with just enough

depth to give a classical sound. Also, Carreras’ tone paradoxically, even in

the higher tessitura, seemed to be

extremely dark in timbre. While not unacceptable, the conflux of these factors

undermined Carreras’ success in this repertoire. In La traviata as Alfredo, however, these traits seemed to fit the

role naturally. Though the timbre remained unusually dark for a typical lyric

tenor and the high notes were approached similarly, the role felt more secure

and fully in Carreras’ power. The timbre was thrilling and exciting rather than

a hindrance to singing through the role. The high notes felt more balanced, as

well, although they still employed the hooked-in, simultaneously

overweighty-yet-shouty production. In all, however, Carreras’ was definitely a

comfortable and thrilling Alfredo. Finally, looking at Carreras in perhaps his

most popular dramatic role, the title character of Giordano’s Andrea Chénier, it became apparent the damage Carreras’ choices may have

had on his career. The voice seemed to have inverted, becoming harsh and

metallic instead of rich and dark. Nevertheless, it still had a sense of

pressurized weight to it, though one that no longer manifested in a pleasant

richness but instead in very wide vibrato and raggedness. Essentially, it seems

critics who suggest José Carreras’ voice to be fundamentally lyric might be

correct. The effect of his illness is hard to judge, but the recordings described

all preceded that illness. Instead, the technical flaws of Carreras’ lyric

voice limited his capabilities in the Bel

Canto repertoire and its dark, rich timbre made the temptation of spinto and dramatic repertoire seem

dangerously appropriate. This analysis does not reflect positively on Carreras,

but he did sound divine as Alfredo, and at a meta-artistic level the idea that

the force, raggedness, and degradation of Carreras’ voice represented many of

the characters he played is intriguing.

Analyzing Thill and Carreras against

a baseline of such singers as Björling, Pavarotti, or Wunderlich suggests that those

tenors with greatest versatility sit on the lirico-spinto

borderline. While not a direct analogy, the borderline of lirico-spinto is reminiscent of the most versatile female singers,

who, on a larger scale, were also on the heavier side of the spectrum, allowing

them to tackle both lyric and dramatic soprano and even mezzo-soprano roles. This

larger scale for female singers, however, encompassing switches not only

between intra-voice type Fächer but

also between primary voice types as well, compared with tenors switching Fächer only within their own voice type,

outlines a trend of decreasing versatility proportional with the range of the

voice.

Men with deeper voices and

sufficient versatility are somewhat elusive. That elusiveness further supports

the argument that versatility declines proportionally with the depth of the

voice. Indeed, the trend continues within the low voices, as baritones seem

more disposed to versatility than basses. Even among these less versatile low

voices, however, it remains true that it is the heavier, somewhat dramatic

voices that are capable of the most versatile careers.

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau is often

considered by many to be (at least one of) the best baritone(s) in the recorded

era. It was surprising, therefore, that his performance of the title role of

Verdi’s Rigoletto, a cornerstone of

the heavier baritone repertoire, was not particularly appealing. Fischer-Dieskau

lacked the almost tenoral ring typical of so-called Verdi baritones. At some of

the tenderest moments his innate sense of legato

carried him through, but on the whole the voice felt belabored and forced,

leading to an almost frayed sound. As the Count in the film version of Mozart’s

Le nozze di Figaro, Fischer-Dieskau

brought the only reasonable acting to a production drenched in poor, almost

slapstick comedy. He sang the role almost as he might have sung art song. The

sense of belabored production fell away, and the recitatives were

uncharacteristically interesting while the arias were full of verve. Finally,

as might be expected based on reputation, Fischer-Dieskau’s performance of

Schubert’s Winterreise with Alfred

Brendel was comparatively the most impressive. Fischer-Dieskau’s velvety tone

was beautiful, caressing and piano or

insistent and forte, utilizing all

the stylistic differentiation imaginable to portray the different sentiments

wrapped up in the masterpiece song cycle. The versatility of Fischer-Dieskau’s

career is unquestionable. He was successful in a wide variety of repertoire. Nonetheless,

because Fischer-Dieskau’s voice was fundamentally lyric, it may not have fallen

in the versatility-prone lirico-spinto

region, limiting him in roles such as Rigoletto but benefiting his work in

lighter repertoire.

While versatility was still present

in the work of Fischer-Dieskau, a baritone, it became yet more elusive looking

at still deeper voices. George London, generally considered to be in the

nebulous category of “bass-baritone,” however, does fit. Possessing a fairly

large, dramatic voice, he also fit in the range to succeed at both lighter,

more baritonal roles and also heavier, bass-baritonal roles. In the title role

of Mozart’s Don Giovanni George

London brought a warm, creamy, explosive production that definitely emphasized

the galvanized dangerousness of the character, though it undersold the more

vibrantly electric sexual virility Don Giovanni also possesses. The voice’s

undeniable intensity seemed best suited to heavier roles. In the title roles of

both Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov and Wagner’s Der fliegende Holländer this sound was

perfectly appropriate, granting a commanding, almost otherworldly boom to roles

removed from the everyday life of the common person: a mad emperor and a

supernatural ship’s captain. John T. Gates, Visiting Assistant Professor of

Voice at Lawrence University, remarks that bass voices do not work like most

other voice types and that bigger, heavier voices are almost always preferred.

George London, however, demonstrates that heavy voices with the capability to

tackle lighter repertoire still seem to be the ones that succeed in versatility,

though perhaps because of the unusual situation for bass voices London’s

performance of Don Giovanni was somewhat hindered.

The voice of Giorgio Tozzi, who sang

a vast variety of opera roles, as well as music outside of opera, also supports

a similar conclusion. Tozzi, though defined as leaning more toward the bass

side of bass-baritone, was at least as versatile as London. Opposite London in

the same performance of Der fliegende

Holländer in the character role of Daland (though he sang the Dutchman in

his career, as well), also in the title role of Boris Godunov, and as the

bass soloist in Handel’s Messiah, Tozzi

consistently possessed a large, rich voice. If anything, however, Tozzi’s voice

sounded lighter in timbre, cooler, and more metallic than London’s voice. Tozzi

succeeded throughout this diverse repertoire by changing his style of singing

from expressively conversational in character roles to smooth, legato, and nobly refined in fully-sung

roles such as the Dutchman or Boris, and finally light and free in the

coloratura of Handel’s Messiah. Tozzi

was highly regarded as reliable and constant in his production, a true artist

capable in a vast variety of repertoire. Here, he serves as a perfect

conclusion to the theory. Though Tozzi suffered from the same deep-voice issue

as London, limiting his overall versatility compared to higher voices, his

lighter timbre and more supple voice compared to London’s supposedly more

baritonal bass-baritone actually allowed him greater versatility, in line with

the theory that dramatic voices that sit on the margin are those most capable

of sustaining heavier repertoire while also cherry-picking lighter repertoire.

As male voices get deeper, total

versatility compared to other voice types diminishes. Like those other voice

types, however, it is the somewhat heavier voices that sit between lyric and spinto that seem most successful in a

broad range of roles. Fischer-Dieskau was not entirely successful in heavier

baritone roles due to his fundamentally lyric voice and expressive style of

production, but nevertheless was close enough to succeed and did so in a fairly

broad range of repertoire. Deeper still, George London and Giorgio Tozzi, demonstrated

that, though hampered by the need for bass-like voices to be large and robust,

through unique vocal characteristics and exceptional skill, they could use

their place on the margin to succeed in a range of roles in the baritonal,

bass-baritonal, and bass ranges, illustrating, along with Fischer-Dieskau, both

declining versatility proportional with their ranges and also the capability to

access versatility through their somewhat heavier voices within their voice

types.

Categorizing voice types and

subdividing them using the Fächer and

other systems serves important purposes such as allowing houses to select

singers, singers to judge appropriate repertoire for their careers, and

enthusiasts to know what kind of singer they might like in a performance of

given repertoire. Voices definitely do break down into rough categories. Still,

the human voice is to a large extent a sliding scale of capabilities, and

strict definition into these groupings cannot be reduced to hard limits based

on tessitura, range extremes, vocal

size, or timbre. A general conclusion, however, seems to be that moderately

heavy lirico-spinto type voices among

female voice types, tenors, and deeper male voice types tend to lend themselves

most successfully to versatility even as that versatility decreases

proportionally with the depth of those groups overall.

Most sopranos and mezzo-sopranos who

succeeded in switching between Fächer

or even between the two broader voice types generally were capable of singing

the heavy soprano or mezzo-soprano repertoire but possessed unique abilities to

master lighter repertoire, as well. By comparison, lirico-spinto tenors similarly seem the most capable of switching

between tenor Fächer but tenors,

unlike the women, are much less likely to successfully switch into another voice

type entirely, especially in the middle of a career. Baritones, bass-baritones,

and basses suffer under acoustic requirements for deeper voices to possess

great size in order to carry and be thrilling in roles often portraying figures

such as fathers, gods, and supernatural beings. Nevertheless, even within these

voice types singers with sufficient thrust to bear out those roles while also

tackling lighter repertoire still managed to sing versatile careers, unifying

the theory.

Exactly what trait offers any given

singer the ability to pursue repertoire from multiple Fächer or even primary voice types is perhaps impossible to say. These

examples of singers known for their versatility, however, offer some insights

as to how specific traits help or hinder careers spanning a broad range of

repertoire. Those conclusions lead to a theory, albeit necessarily rough, of the

prerequisites for versatility. Versatility seems inversely proportional to the

range of voices, with deeper voices less versatile than light ones, but within

the categories of women, tenors, and darker male voices it is the roughly lirico-spinto voices that are most

predisposed toward versatile capabilities. It may be impossible to reconcile

the natural rigidity of a vocal categorization system that accurately describes

so many singers with unusual vocalists capable of successfully performing a

broader range or repertoire. Perhaps the most useful finding of this study is

to reinforce this fact, demonstrating both the benefits and limitations of that

very classification system.

Works

Consulted

Hines,

Jerome. Great Singers on Great Singing.

New York: Doubleday & Company. 1982.

Jacobson,

Robert M. Opera People. New York: The

Vendome Press. 1982.

Thank you also to the voice

faculty of Lawrence University for their recommendations of singers who fit the

parameters of this project and to Bonnie Koestner for her support in this

endeavor and her wealth of knowledge on the topic.

[1] This essay acts as a conclusion to this

study’s reports on versatile singers and assumes some familiarity with the observations

of individual singers. Descriptions of singers’ voices and references to

specific repertoire are therefore not comprehensive and are raised only where

they support the broader conclusions of the study as a whole. All singers’

careers are addressed in the past tense as no singer is currently singing the

kind of repertoire for which they were known.

Comments

Post a Comment