La musica di dolore

Forgive the tardiness of this post. It is my intention that, while here at school, I post at least once a week. Once I'm off for the summer, I hope to post more often. However, this past week I experienced a painful breakup that somewhat delayed my ability to keep up with my schedule. Nonetheless, I'm back, and using that situation as inspiration for this post. The title, for those less familiar with Italian, means "the music of pain." This post will focus on opera music that deals with the loss of love and the exquisite, unique pain that brings.

Forgive the tardiness of this post. It is my intention that, while here at school, I post at least once a week. Once I'm off for the summer, I hope to post more often. However, this past week I experienced a painful breakup that somewhat delayed my ability to keep up with my schedule. Nonetheless, I'm back, and using that situation as inspiration for this post. The title, for those less familiar with Italian, means "the music of pain." This post will focus on opera music that deals with the loss of love and the exquisite, unique pain that brings.First of all, I would like to address what may become a perceived inequality in this post. There seem to be a lot more arias of this type for certain voice types than for others. Tenors, in particular seem to come in at first place, followed by sopranos. The bias here is due, first and foremost, to the way roles are assigned. Basses and baritones tend to be villains, father-figures, or older men in positions of power. Thus, there are significantly fewer operas in which these men lose love, at least in a romantic sense. Mezzo-sopranos, though perhaps they would chagrin me the comment, tend to play the role of the temptress more often than the ingenue lover. Hence, that leaves us with sopranos and tenors primarily filling this role. The disparity between these two voice types is accounted for by a simple, if morbid fact. The sopranos tend not to explain that their love is lost, rather, it tends to be inherent in their deaths.

Going forward, I will look at a few different arias that deal with this emotion. There are situations, I will point out, where lover mourn the future loss of their love together. However, for simplicity's sake (and that isn't the experience through which I'm going!) I'm going to stick to arias. I will supply the names of singers who I personally find to have crafted some of the most emotional recordings. Note of course, that you should form your own opinions of all the great performers, and that the true mark of their artistry is not what they did in the studio but rather on stage!

Going forward, I will look at a few different arias that deal with this emotion. There are situations, I will point out, where lover mourn the future loss of their love together. However, for simplicity's sake (and that isn't the experience through which I'm going!) I'm going to stick to arias. I will supply the names of singers who I personally find to have crafted some of the most emotional recordings. Note of course, that you should form your own opinions of all the great performers, and that the true mark of their artistry is not what they did in the studio but rather on stage!The first, and perhaps one of the best for capturing this feeling of loss, is "E lucevan le stelle" from Puccini's Tosca. As Mario Cavaradossi awaits his execution, he recalls dreamily his days of love with Tosca and mourns losing that love with his coming death.

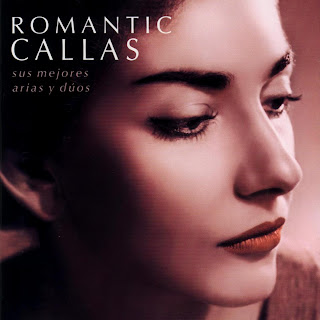

Another piece in a similar vein also hails from the very same Tosca but is sung by Tosca herself as she contemplates Mario's pending execution. The piece captures well the feeling of helplessness often experienced at the end of a relationship, whether it is ended by death or a simple separation. Though many often are skeptical of her tone, I must say that I find Maria Callas puts a great deal of emotion into her interpretation. She gives the piece the beauty it must have (it is a prayer to God, and a vigil for a lover) but there's the tinge there that she's in inexorable, inescapable pain, and cannot understand why she must endure it.

These first two pieces may already have begun to show a sort of pattern in the emotional content of these pieces. There often seems to be some sort of dichotomy between the love lost, and the pain or anger of losing the love. Some pieces, like "E lucevan le stelle" fall more on the sweet side, others, like "Vesti la giubba," from Leoncavallo's Pagliacci carry the full weight of anger. For this piece, though I love Björling's soaring tone in the fortissimo section of the aria, I cannot give him the crown. For that, I feel the need to look far, far back, to Mario Del Monaco. This is certainly an aria for darker, heavier dramatic voices. Of those, Del Monaco takes the cake for me. He sings the aria with audacity, which is appropriate given his anger at the infidelity of his wife with a fellow troupe-member. The mocking laughter in the beginning has a somewhat gut-wrenching feeling in their irony. The vocal cries and vibrant forte bring out the emotions in the middle of the aria, and the half-laughing, half-crying at the end throws the laughter of the beginning in the face of the audience, bringing home just how sickening the position Pagliacci must suffer is.

Most of the arias discussed to date have been from the Romantic Era, in sharp contrast to that, the next piece is "Qual farfalla" from Leonardo Leo's baroque opera Zenobia in Palmira. Because of the antiquity and obscurity of this piece, the only recording of which I know is on Cecilia Bartoli's Sacrificium, an album I intend to discuss in a future post. I would love to hear other interpretations if anyone can recommend to me where to find them. Despite the peculiar origins of the tune, it is an excellent representation of the Baroque take on the aria regarding lost love. The text, about a butterfly being lured to a flame and burned by it, characterizes the progression of many relationships from inescapable ardor to scorching pain. It is important to understand that "Qual farfalla" was written for the castrato voice and that Bartoli's interpretation is an approximation of the style and the quality such a singer might have possessed. Nonetheless, the aria paints a beautiful floating line requiring amazing breath support. This gives the feeling of a fluttering butterfly, drawn to the flame, flitting around it just as trills flit around pitches on the score.

The last piece for this post is actually not from an opera, but is the Neapolitan art song, "Core 'ngrato" by Salvatore Cardillo originally composed in 1911 for Enrico Caruso. Though Caruso, in this fashion, holds a definitive version of the piece, there are other versions that, in my opinion, even better capture the emotion of the piece. The two voices I most enjoyed listening to were Corelli in concert late in his career. I could only find this on YouTube here. This version, particularly due to a darkening in color due to age, has a very warm feel to it. A slightly more raw and emotional performance comes from Mario Del Monaco.

This finishes up the post about sad songs. Hopefully no one has to hear them and identify with them too often (particularly not as dramatically as in many of the operas!)!

Comments

Post a Comment