Maria Callas & Victoria de los Angeles

Maria

Callas & Victoria de los Angeles

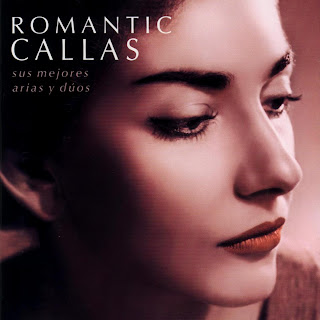

Maria Callas

Maria

Callas’ renown as La Divina is of

course legendary. Her legacy, however, is equally clearly controversial. Walter

Legge, producer of many of her recordings, describes her vocal assets as part

of a larger section on the same in Jürgen Kesting’s Maria Callas. Her three octave range, distinctive timbre, sizable

voice, a potential darkness in the middle range, easy coloratura, and access, if not security in the top notes. Perhaps

even more of note is Kesting’s description of the dichotomy between “good”

voices, lacking in naturally effortless technique but with great artistry, and

“beautiful” voices whose effortless technique seems to be the end in itself.

Kesting asserts that Callas fell into the former category. Kesting repeatedly

addresses issues of style in relation to this categorization, noting Callas’

abilities to execute pianissimi, portamenti, true Bel Canto coloratura, and

emotional shading. He notes, however, that the core voice seemed flawed in some

significant ways, seeming shrill, sometimes harsh, insecure and wobbly in the

top, and sometimes lacking in power at the very bottom.

This is

borne out both by reviews of Callas’ work and my own analysis of her live

performances in Lucia di Lammermoor

at the Metropolitan Opera in 1956 and of Tosca

in 1965 in Parigi, as well as her studio recording of Carmen under Georges Prêtre. In listening to Callas’ Bel Canto work it was clear how her

artistry revived the style and repertoire of that time period. Contrary to

earlier recordings, Callas clearly articulated a style that did not merely

layer Puccinian verismo on top of

earlier composer’s music. Instead, her substantial use of dynamics, mellifluous

lines and phrasing, and vocal shading set the genre apart in a way that even

today, with the focus on more “accurate” historical practice, seems lacking in

the performance of this repertoire. Particularly impressive to me was this technique

of vocal shading (perhaps called tinta

in some circles), as it is something that, done infrequently, usually is done,

in a very dramatic way, in Verismo

opera, rather than subtly as Callas employed it. Nowhere was this clearer, of

course, than the mad scene. From a personal standpoint, however, the sometimes

harsh, almost reedy sound of Callas’ voice mixed with shrill top notes was

dissatisfying from a standpoint of pure vocal aesthetics. It is not a voice

that I particularly wanted to listen to for its sheer vocal beauty.

When

listening to Callas in Tosca, I was met by the remarkable discovery that the

style and interpretation is, in many ways, the same. Where I might expect,

normally, to hear a slightly older singer with a more developed voice produce a

fuller sound as Tosca rather than Lucia, or even to simply let go more on the

more sustained passages, this only occurred to a small extent with Callas.

While in a few fortissimo portions

her voice did take on a tone more typical of a lead soprano in a Puccini opera,

she invariably reverted to the smaller, more precise, and often thinner, almost

nasal tone she used in Lucia. This tone did seem to carry. Harold C.

Schonberg’s review of her 1965 Tosca

at the Met more or less sums up my feelings on her performance in the role. He

mentions the same dichotomy as Kesting, that Callas’ Tosca was exquisitely

interpreted, beautifully phrased and with ample use of emotion displayed

through vocal means, but lacking in the full, round tone that is vocally

satisfying especially in this repertoire.

Callas’

foray into mezzo-soprano repertoire was intriguing in contrast with the

preceding two operas. Where Callas’ voice seemed to fit the preceding two roles

in a fairly uniform manner, almost bending the repertoire to her voice rather

than the other way around, a perceptible difference was noticeable in Carmen. The easiest description I can

find is that it simply sounds more comfortable. The same tactics are there, the

same Callas artistry and, to an extent, the same Callas sound, made in some

cases even more nasal by the French. Still, while the tone may not be

substantially more full, it seems to have more body and less of a sense of

detachment. A writer for the Times in

London noted the same experience at a 1962 recital featuring mezzo-soprano

repertoire in contrast with soprano repertoire. Hence, Carmen retained the

interpretive glory present in both Lucia and

Tosca while seeming to ease both

Callas’ singing and my listening experience. It is hard to tell how Callas’

Carmen would have sounded in the house, but a rough estimation seems to suggest

she would at least have been able to pull it off.

In

summary, there seem to be some intriguing possibilities for why Callas ended up

the way she did. Perhaps, as some have suggested, she was just a mezzo-soprano

with exceptional range and agility in the soprano range, explaining why she

sounds more comfortable in mezzo-soprano repertoire despite her fame in soprano

roles. There are indeed examples of such singers both in the past and today.

Callas’ ability to sustain some of the highest roles in the repertory as well

as those like Tosca that require both

range and staying power in contrast with the lighter voices of many of these

kinds of mezzo-sopranos, seem to undercut this philosophy, however. It may be

that her sudden and severe weight loss had something to do with the change, as

well. My suggestion, however, is that while that may have been a component both

physically and psychologically, her choice of repertoire and technique may

ultimately have been responsible for the result. Recordings of Callas in her

early Wagnerian bouts are not really extant as far as I can tell, but in order

for her to merely perform Isolde or Brünnhilde, a quite large voice and great

stamina would have been necessary. After this analysis, I am very intrigued by

the notion supported by some that Callas actually possessed the sort of

dramatic soprano or high mezzo-soprano voice that sits on the borderline but,

perhaps unique to her case, has unusual range. If, then, Callas cultivated a

technique that was off-the-voice or used only a fraction of it, her ability to

be heard in nearly any role over an orchestra no matter what kind of shading

she did but with a relatively unsatisfying tone quality would make sense. It is

clear, even from scathing portrayals such as in “Maria Callas: Great

Interpreter; Dysfunctional Vocalist” in Queer

Voices: Technologies, Vocalities, and the Musical Flaw by Freya Jarman-Ivens,

that Callas’ interpretive abilities were impressive vocally. Combined with her

impressive stage presence and physical acing abilities, which can be viewed in

excerpts if not in whole roles, it is clear why she deserves her acclaim in

that regard, and why her legacy may have been bred in a generation that saw,

rather than merely heard, her perform.

Victoria

de los Angeles

I was already somewhat familiar with Victoria de los Angeles

because of her recordings with Jussi Björling in the Verismo repertory. I was less familiar with her lighter repertoire,

however. After listening to her 1954 performance in the title role of Manon, I was met with quite a surprise.

To some extent, de los Angeles reminded me of Maria Callas. The tone she

employed was quite a bit tighter in vibrato than that she employs in heavier

repertoire (though certainly parts of Manon are not the lightest). I was

impressed, however, by the level of phrasing and play with dynamics that de los

Angeles employed here. I do not want to say that these elements are lacking in

her heavier repertoire, but merely that here they are clearly the focus, with

tonal splendor taking a sort of back seat. Nonetheless, the tone seemed a bit

less supported, a bit less full, and perhaps slightly harsher. I will admit to

preferring it to Callas’ tone, nonetheless. It does support the notion in the

preceding section though, that this result may occur with larger soprano voices

focusing on hushed phrasing and artistry rather than on pure vocal technique.

In Puccini, both as Madame Butterfly and especially as Mimì,

the voice truly blossoms. None of the Callas-like sound remains, and it is

clear that a substantial, though not massive (although these were not live

recordings), voice with adequate ring and a warm, supple tone is particularly

fitting for this repertoire. Indeed, it almost seems like this is perhaps de

los Angeles’ ideal spot. For me personally, I might feel the voice lacked a

more steely, ringing sound for some Verdi, and for repertoire of different weights

it might not have been entirely appropriate. The phrasing and artistry are not

absent, but the voice itself does more of the work in this repertoire. Again,

however, this seems fitting. Somehow de los Angeles’ tone, combined with

Puccini’s melodies, seems to convey the emotions necessary without much

modification. A 1957 Times review of

her as Butterfly suggests exactly this, although it finds the interpretation to

be “cold.” I suspect this is an aberration, however, as other reviews, to be

discussed shortly, point to the opposite in almost all of de los Angeles’ work.

Victoria de los Angeles’ final career move as far as

repertoire was to perform and record Elisabeth in Tannhäuser before turning to

a substantial recital career punctuated at times by continued opera

involvement. Elisabeth is not comparable in weight to the heavy Wagner

sopranos, but it is a significant foray by de los Angeles into German

repertoire, and was interesting to compare to her work in Puccini repertoire. I

found her technique to be largely similar between the two, although, almost

peculiarly, she seems actually to employ more phrasing, use of dynamics, and

vocal shading than in the Puccini operas. This makes sense to some extent,

however, as Wagner’s music was meant to be more holistic dramatically, whereas

Puccini’s music really does seem to be more melodically focused on the voice.

Victoria de los Angeles’ final career move as far as

repertoire was to perform and record Elisabeth in Tannhäuser before turning to

a substantial recital career punctuated at times by continued opera

involvement. Elisabeth is not comparable in weight to the heavy Wagner

sopranos, but it is a significant foray by de los Angeles into German

repertoire, and was interesting to compare to her work in Puccini repertoire. I

found her technique to be largely similar between the two, although, almost

peculiarly, she seems actually to employ more phrasing, use of dynamics, and

vocal shading than in the Puccini operas. This makes sense to some extent,

however, as Wagner’s music was meant to be more holistic dramatically, whereas

Puccini’s music really does seem to be more melodically focused on the voice.

Most of the reviews easily accessible for Victoria de los

Angeles’ career actually focus on her extensive recital engagements. Her

repertoire for these appears to be varied and thus quite interesting. Mentioned

in reviews were Spanish opera and zarzuela,

Rossini, Schubert, Handel, Ravel, and even such rarities as Lully and

Pergolesi. Of course much less of this is available recorded live. Nonetheless,

the reviews are, on the whole, quite positive. Occasional mentions of musical

insecurity, vocal thinness, especially with age, and glum interpretation do

crop up. This is fair, however. Reviews of Maria Callas make little emphasis,

other than simply stating the obvious, about a horrible night because she was

already so polarizing and so unusual. De los Angeles’ record much more

accurately reflects that which I would expect for any artist. Some repertoire

that might have been poorly selected, some nights when she just was not feeling

the music the way she might have, some occasional vocal troubles, yes.

Fundamentally, however, the glossy warmth of the tone and the strength of the

interpretation, combined with a vivacious, youthful stage presence were the

norm and far outweighed these occasional foibles.

As a closing note, being a native Spaniard and having the

capability, de los Angeles also tried her hand with Carmen, and did so both

live and in the studio. Though I did not watch or listen to a full performance

of this, I did actually watch a black and white video of excerpts performed

live. De los Angeles handled the role ably, seeming to carry fine over the

orchestra despite the lower range and still creating a pleasant tone. As some

reviewers note, however, the voice did not quite possess the same staying power

in the lower registers, and perhaps took a bit of a toll on the instrument (one

reviewer, for instance, suggested that singing the Habañera once and then again as an encore was ill-advised). From my

own perspective, it seemed like it was fine, but lacked the smoky, sultry

quality that some true mezzo-sopranos bring to the role. Matching this lighter

vocal weight though, de dos Angeles performed what reviewers call a

naturalistically, truly Spanish interpretation that played up the desultory,

teasing nature of Carmen rather than the potential for raw sexual appeal, which

is sometimes overdone.

I personally believe that Maria was high Mezzo as well with an intriguing dark color to her voice. I'm not well versed in her work but l have seen her at work supposedly singing dramatic Soprano I couldn't believe what l was hearing. She was clearly belting as contemporary singers do! I don't think natural dramatic voices need to push their voices write that way to doing large and powerful.

ReplyDeleteIn the Opera world, chest tones are considered ugly. Soprano voices are instructed to use their high register as soon as possible, by blending their voice, giving them a brighter, ringy tone in their in general--they have notoriously long middle registers. Mezzo Sopranos with their naturally lower voices and heavy, chesty sound in general are also told to reign in the chest voice. In fact, it's considered ugly and even uncouth in a woman (for some reason only contraltos are expected and admired to perform almost exclusively in chest voice). The goal is to develop a tone and a balanced and a seamless voice.

Remember Callas was criticised for many things. Her different voices, her shameless useuse chest voice, her aural shouting, her timbre strange, incomprehensible, uncompromising... Downright ugly!

Truthfully I find her a really gutsy singer and a fantastic interpreter of music and every role she played. Chest voice in her singing was what made her sound dramatic and exciting. She dared to be different. She was no wall flower, she was not called a diva for nothing.

In contemporary music, as the dramatic Soprano voice is quite rare, l adore Jill Scott. Her voice is so rich, dark, womanly and full, she can easily pass for a Mezzo Soprano. Her naturally large voice easily over powered other featured singers (even the natural Mezzo-sopranos) at an event honouring American ex President Obama. Her rendition of "Golden" was so memorable for me.

Good blog, it brings back memories of Maria Callas....she once said:" After every performance I would think what could have been done better, to make it better in the next performance and how things can be done differently. I am never satisfied with my performance and will try to improve it next time."

ReplyDeleteI tried to write a blog about her, hope you like it: http://stenote.blogspot.com/2017/11/an-interview-with-maria.htmlhttp://stenote.blogspot.com/2017/11/an-interview-with-maria.html